Vancouver Vet Tells It Like It Is

November, 2000

Having worked for one of the best veterinarians I ever met, Charles Chappelle in Fort Collins, Colorado, my standards for veterinary competence have been pretty high. Usually I've done Ok, but the fellow I'm about to immortalize was uniquely different.

In Crom's thirteen years, we encountered everything from an ex-rodeo cowboy whose approach was, "How is this dog like a horse?" (not a bad approach in Crom's case, but skewed nonetheless) to the firm, gentle competence of the doctors at the Boulder emergency pet care office. I've had doctors who treated me like an incompetent hysteric and Crom like an interesting carcass. We've had our share of jerks and incompetents, like the Salt Lake fellow who, after I described an episode like an epileptic seizure, trying to find out how I should handle that situation if it recurred, offered this: "Oh, yeah, that's a seizure. Big dogs have them for some reason. They just come out of it. Or die."

Good Doctors

Since what follows is a hatchet job on a miserable boob who is in the wrong profession, let me add this disclaimer: Most of the vets I have known have been good, competent, kind people. Crom's last vet, Dr. Jennifer Schwind of Baseline Animal Hospital, was the best of them, and her husband and partner is the male vet who gave Crom his last looking over before we left for Vancouver. He's described below as unthreatened by Crom's size and not laden with the male need to prove anything to big dogs.

The two of them and their veterinary assistant, Shannon, were all Crom and I could ask for in our last years, the best of a series of good care providers and friends to our four-legged companions. Their strength, intelligence, good will, and love for animals are less common than should be. Like Doctor Chappelle, they epitomize veterinary medicine.

We've dealt with veterinary commonplaces like the physician who offered to keep Crom for "observation" after spending hours trying to diagnose a viral infection that had rendered him comatose. I asked if there was anything they could do for him that they hadn't already done, and he said there was not. So I said that if Crom was going to die, it would not be alone in a cage, and we went home to wait for the last antibiotic to do its work. Or not. Fortunately, it did.

Over the years, we gravitated toward women, who don't get a testosterone rush when they see a big male dog. We had a couple of good male doctors, though. Our last physician back home before leaving for Vancouver was a man, the husband of his partner. She had looked at Crom the week before and proposed the "low residue" diet that seemed to control the stomach pains Crom had been having for months. We had come back on a minor emergency and it was her day off.

Her husband was, like her, a reassuring combination of honesty, candor, and empathy. He didn't, like so many men, seem to feel that he needed to show the dog (and, of course, me) how strong and overbearing he was. Crom is not a bully, but he will not abide bullying. I was so impressed that when we returned to Colorado, this couple become our vets through the terrible day of Crom's death four years later.

My first experience with a Canadian vet may have capped every incompetency and stupidity I've encountered in decades of visiting veterinarians. I mention that he was Canadian because that fact was important to him, as you will see. For all I know, he was an immigrant like me.

Since arriving, I had run out of the special food that Crom had been eating that summer, and this vet clinic was in the neighborhood, so I dropped by to see if they had it. We routinely weigh in every time we visit a vet, so I weighed Crom while talking to the receptionist. He'd been stressed for more than a week, with serious diarrhea, and he had lost three pounds on the trip, in the two weeks since he had his "immigrant health check" in Colorado. Since he had consistently weighed 124-126 for nearly eight of his nine years, I was concerned. I decided to have him see the vet as well.

We came back that afternoon for our appointment. Ushered into an examining room, we waited. Crom examined the photograph of an eagle on the wall. (Dogs don't understand 2D images, of course, blah, blah, but that's another topic.) We talked about how to be good for a vet. I had forgotten to bring his muzzle.

|

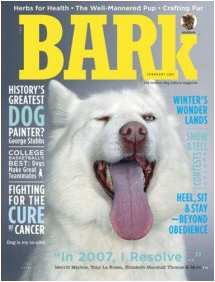

I discovered Bark |

"What seems to be the problem?"

"I need to get him a low residue dogfood. We're out of what I brought with me. And he had some uncharacteristic weight loss on the trip, so — "

"Well, I'm not going to give you low residue dog food. I'm going to get him on a low fat diet right now. He's fifteen pounds overweight." He is holding the chart with Crom's age, breed, and weight on it.

"He's always weighed one-twenty-five — " and he's down to one-twenty-two, I added mentally as he interrupted again.

"Then he's always been overweight. Look, let's say we could keep him alive another four years. Ridiculous, I know, but bear with me. If we have to put him asleep in a year or two because of his arthritis, I don't want you to feel guilty because you let his weight exacerbate the arthritis."

He had "diagnosed" the arthritis without doing anything to the dog, who was sitting quietly at my side. Impressive. Of course, Crom does have arthritis, so I couldn't quibble about his diagnostic leaps and psychic powers.

"He needed the low residue for a GI problem," I explained. In fact, we'd been through five months and nearly a thousand dollars in tests to get him stabilized. We had finally determined that he was allergic to cheese, but the food did seem to be doing him good generally. I started to tell the vet this. He interrupted me again.

"What he needs is to lose fifteen pounds. And don't think exercise will do it. Does he get any exercise?"

"We walk about ten miles a week, but he's been cutting down."

"Good. Exercise will just make the arthritis worse. And this climate. It takes years off a big dog's life. People think because we have mild winters, it's good for dogs, but the damp just kills them. I lose more older dogs to arthritis than to cancer, heart conditions — you name it — combined. We had a mild winter last year. So people forget what it's like. A good wet winter and he won't be able to walk."

I nod. We won't be staying.

By now, he's actually looked at and touched the dog, finally. Not before insisting that we put Crom on the table, which worries Crom. He's used to being very good on the floor, where nobody gets acrophobic and he will lie still and even roll over on demand. This jerk didn't even ask. He and I heft the dog up and he pushes and probes while I try to keep Crom calm.

He's talking nice to the dog, just like they taught him in vet school. It's probably on a checklist. Or a sampler over his desk. He palpates joints, confirming a minor problem in the knee of Crom's left rear leg. He checks the heartbeat and breathing. The reassuring commentary continues; mumbles for the dog, for me: "A dog this big is lucky to live ten years." Crom is nine; he made thirteen.

He steps away, fondling the stethoscope. "Have you got him on medication?"

Crom's feet keep sliding on the greasy linoleum, and he doesn't want to stand up. I let him sit. The vet had me put my hand on Crom's lower abdomen to keep him standing for the examination. I'm not sure why he had to be standing, or why this healthy adult male (he could live another ten years, unless he smokes or irritates a little old lady with a sick poodle and a gun) can't kneel down beside a dog standing comfortably on the floor. Arthritis? Maybe his wife will have him put to sleep. I've begun to wonder if I have an obligation to be civil. Of course, I'll need his help getting Crom off the damned table. So I try civility:

"He takes Rimadyl — "

"I'm going to put him on Medi-cam. Americans like Rimadyl. Here we use Medi-cam. It's expensive, but you know, you weigh your options. You weigh the cost against the amount of relief. You try it for a while and you say, 'Am I getting value for my dollar?' If you're spending a lot and not getting much relief, then it's time to put him down."

It doesn't escape my notice that he seems to think the medicine's primary task is to give me relief. But primarily I'm wondering why this guy is obsessed with killing my dog. It's not so much that I don't know Crom is unlikely to live five more years, it's this relentless insistence that we need to talk about his death. Does he think I'm afraid to face Crom's mortality? I live with it every day. But I had pretty much stopped paying attention to guy's chatter. I would not bother to tell him what he could do with his "Medi-Cam." I was focused on keeping Crom calm and on how to get out of this situation without wasting too much money. It turned out the first bag (of the low-fat dogfood) is free, so I took it. But "free" wasn't much of a value; Crom wouldn't eat it. Eventually I tossed it out.

I'm murmuring to Crom, who is standing again and looks worried, his back legs slightly squatting to control the slipping and sliding. And the vet is telling me about Medi-cam, or whatever it is. It's sprayed on the dog's food. He hasn't given me any reason to think it's any better than the Rimadyl I'm already using.

"What's in it?" I ask after more polite nodding. "The Medi-cam?"

"It's a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory. You put him on good medication, take care of his diet, and you can probably keep him comfortable for another year or two. Are you giving him vitamins?"

"He gets Comfort. It's an antioxidant vitamin package." And Rimadyl is a "non-steroidal anti-inflammatory," I'm thinking: probably the same active ingredients and buffers. Rimadyl's not cheap, but it works fine. He doesn't tell me anything useful about his wonderful spray, except that it's expensive, wastefully delivered (how much do you lose when you spray it?), and Canadian.

"I'm going to put him on...." At this point, I ceased utterly to listen. Clearly nothing I had done for this dog in nine years was correct: wrong painkillers, wrong vitamins, too much exercise, too much food, wrong food. It was indeed a miracle that Crom was alive at all. How fortunate that we have fallen into his capable hands. We would, of course, obey his every command and hope for the best.

I watched his lips move, as if attentive, while he described a Canadian vitamin he was going to make me give my dog instead of the Comfort pills he was currently on. Neither the painkiller nor the vitamin supplement have anything to do with stress or weight loss, as I do not bother to point out. The stress and weight loss have been completely ignored, brushed aside irrelevancies. I nod at appropriate pauses and intervals.

I think he finally got the picture, that I wasn't buying the Medi-cam, or the vitamins. I don't know if my contempt was penetrating, or he just decided I was stupid. Perhaps he began to comprehend that "we" was me and the dog; it did not include him. He had crossed the room for some reason, leaving me alone to keep Crom on the table. We faced each other silently for an awkward instant, and then he said, "Do you want the food?" I said, "Can you help me get him down?" and he did. We went back to the reception area. The receptionist explained that the sample bag was free, and then I would get a free bag after every — I made a listening face.

I took the free bag, paid $36 for the advice, thanked the nice lady behind the counter, and we left.

I knew Crom was old and going to die. I knew it would be a miracle if he were still alive in five years. I did everything I could to ensure that he would be, and we nearly made it. I had spent that entire summer dealing with his failing health, so bad that I would get up in the night to see if he was alive. Three times we rushed to the emergency care clinic while he was almost paralyzed with abdominal pain. His mortality surrounded me like fog or heat. Sitting in this "doctor's" office I was not worried about next year's arthritis. I was worried about alternating bouts of constipation and diarhhea, weight loss, potential dehydration, despondency and a general look of despair, about vomiting in the car on the way home and politely refusing treats. I was worried about having to leave him somewhere for a few days, and coming back to find him dead or dying. The doctor didn't have any interest in what I was worried about.

I didn't need my nose rubbed in the facts of death. I sat beside Crom for three hours that afternoon when he had the viral infection, after the doctors had given up on him, as he lay comatose. I assumed he would be dead by evening, and I did what I could to see that he would not die alone. The antibiotic kicked in and worked, finally. He lived, and I learned more about mutability, love, and dependency than I needed to know. I have killed things, and I helped him die when the time came. My dog's health may be a bad investment, but I don't need a veterinarian to help me decide that. At least, not this veterinarian.

Three days later, I took Crom in for a free weighing. He'd lost another three pounds, down to one-nineteen, his lowest weight in more than five years. I found myself thinking, A win/win situation. He's losing weight, and it may kill him. The doctor and I should get together for a moment of rejoicing.

Back at my office, I called another vet. We couldn't arrange an appointment, but she said I was dealing with "stress colitis" and the best cure was affection, tranquility, and familiar food. I'll take him in to see her next week. In the days since we talked, he began to eat regularly and his attitude has improved. I took him in anyway, and the other vet was good; we kept her for our six months in Canada.

Dr. Kevorkian, on the other hand, never saw us again. And the good vet convinced me to switch to Medi-Cam or Can or whatever it was. It ravaged Crom's kidneys and liver and we nearly lost him after coming back to Colorado. Oh Canada.

Contents

- In Memoriam: Crom – Introduction

- Our First Years: Sharing Education

- Dog Humor: By, and About

- The Sacred Bunny: Regarding Toys

- Crom's Death: A Sudden Nightmare, March 23, 2004

- Cautery: Finding Link

- Link's Walk: Some Dog-Walking Tips

- Next Year: March 23, 2005

- Dog Wits and Bird Brains–Essays on Animal Intelligences

- Crom's Own Pages–A Tribute to True Love

- Table of Contents — Dogs and Other Creatures